On the evening of April 22, 1915, Allied soldiers crouching in trenches along the northern end of the Ypres salient began choking and gasping for breath as a silent killing agent wafted over from the German line. It was the first use of asphyxiating gas on the battlefield and it sent a wave of panic through the ranks, forcing the Allies back and creating a 5-mile gap in the city’s defense.

At low doses, this chlorine gas damaged the lungs, throat, eyes, and nose, causing difficult and painful breathing. At concentrated levels, it smothered soldiers to death. Later in the year, phosgene gas was introduced to the battlefield, a deadlier but slower-acting agent. By 1917, the Germans had introduced mustard gas to their arsenal, which could penetrate gas masks and ravage the entire body with sores and blisters. It was a wretchedly painful way to die, as Wilfred Owen describes in his poem, “Dulce et Decorum Est,” which reads in part:

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

Throughout World War I, it is estimated some 91,000 soldiers died from chemical weapons. While a small fraction of the 8.5 million battlefield casualties, the psychological impact of gas on troop morale was formidable. It became imperative to alert the entire body of troops the moment gas was detected, affording them the most time to fit gas masks and take necessary defensive precautions. Sentries kept watch in two-hour shifts over No-Man's Land (the ground between opposing armies). When gas was detected, the alarm would sound.

Image: A British gas sentry of the Royal Garrison Artillery on lookout duty with his gas gong near Combles, France, in March 1917. Courtesy: Imperial War Museums.

Image: An improvised gas gong on the Romanian front during World War I.

Gas attack alarms were installed throughout the trenches. These were often primitive in nature; horns, rattles, and relay shouting would transmit the information for hundreds of yards in an instant. Others relied on makeshift gas gongs. These gongs could be made from any sonorous objects at hand, say, a frying pan suspended from a bit of rope or by retrofitting empty large-caliber shell casings with a clapper or metal pipe for striking.

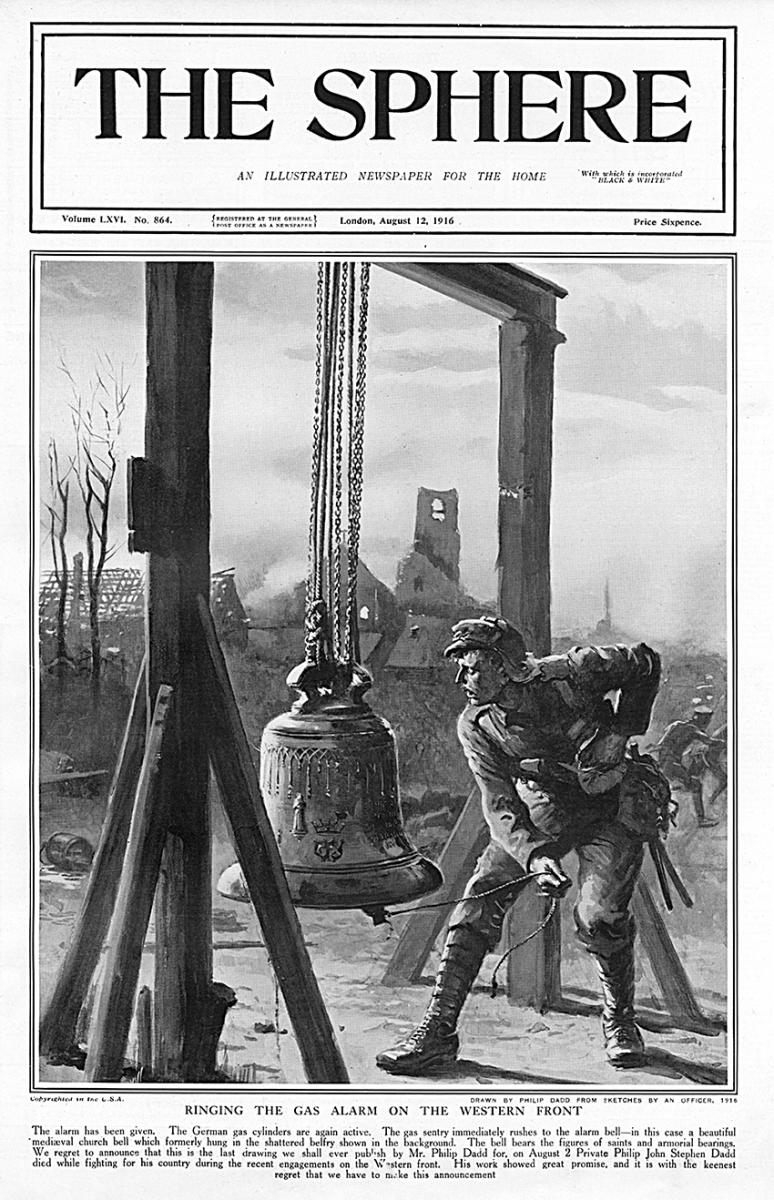

As troops made their way through bombarded villages, some enterprising soldiers would collect bronze bells from the churches they encountered, raising them on wooden frames to ring out. The resonating tones of salvaged bells could penetrate foxholes and trenches, a clear tocsin even in the din of war.

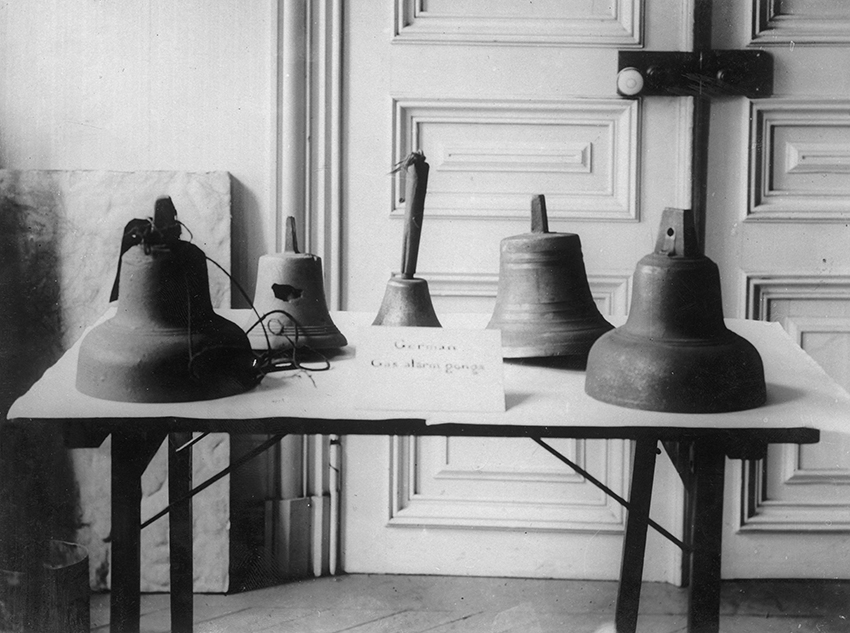

Sinister relics, gas gongs were also coveted trophies on the battlefield, stripping the enemy of a vital communications channel and rendering them vulnerable to future gas attacks.

Image: A gas bell trench alarm post at Beaumont-Hamel in Dec. 1916, with a sentry of the South African Contingent pulling the clapper to give warning. The bell bears a handwritten message in chalk: 'Duck ye nut'.

Image: A British gas sentry rings a medieval church bell bearing figures of saints and armorial insignia (formerly hung in the shattered belfry shown in the background) to alert troops of a German gas attack. This cover image by Philip Dadd for the August 12, 1916, edition of The Sphere, was to be his last. The painter and rifleman was killed in France on August 2, 1916, before publication.

Image: A large bell recovered from a ruined church is suspended between two trees to warn of gas attack on the Western Front during World War I, c. 1916. Image from “The Great World War: A History” Volume VI (1920), edited by Frank A. Mumby. Courtesy: Gresham Publishing Company Ltd., London.

Image: A bronze bell from a destroyed village church is suspended between two trees in the Upper Marne, France, in 1917, and used by Allied forces to warn of impending poison gas attacks.

The legacy of chemical weapon use in warfare

The physical effects of gas exposure were agonizing and could linger within the body, leaving hundreds of thousands of soldiers suffering long after the armistice was signed. Recognizing the devastating nature of gas and chemical weapons, countries across the world gathered in Geneva to ratify the 1925 Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, which banned the use of chemical and biological weapons in war.

Image: Five alarm bells used to warn of gas attacks during World War I, taken by the Allies as war trophies from captured or abandoned German trenches between 1914 and 1918.

Cover image: A gas sentry ringing an alarm bell at Fleurbaix, 15 miles south of Ypres, in June 1916, as photographed by Lt. Ernest Brooks. Courtesy: Imperial War Museums.