Many consider August 1619 to be a significant starting point in the history of slavery in America, when an English privateer ship landed near the British colony of Jamestown, Virginia, looking for food and supplies. For such victuals, the captain traded human cargo: 20 Black people forcibly taken from a Portuguese colony in southwestern Africa. The red stain of slavery in America would continue for the next two and a half centuries.

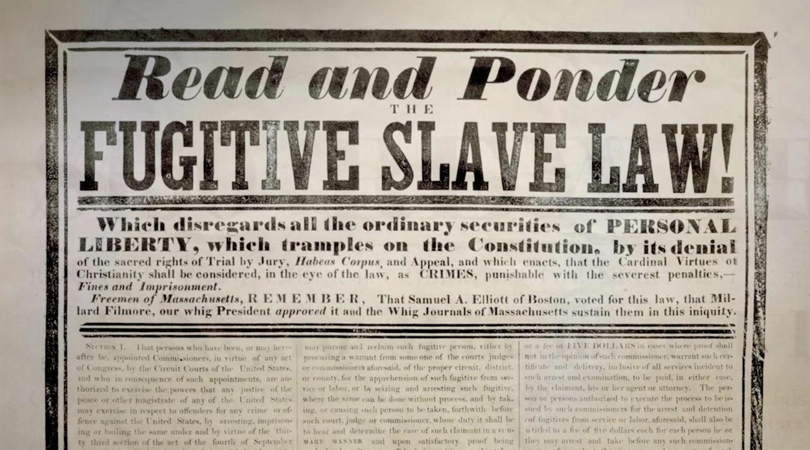

People who wanted to abolish slavery became known as abolitionists. They worked to counter the expanding reliance on slave labor, to halt the Atlantic slave trade, and to liberate those who were enslaved. Abolitionists’ campaigning would culminate in the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) and the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (1865).

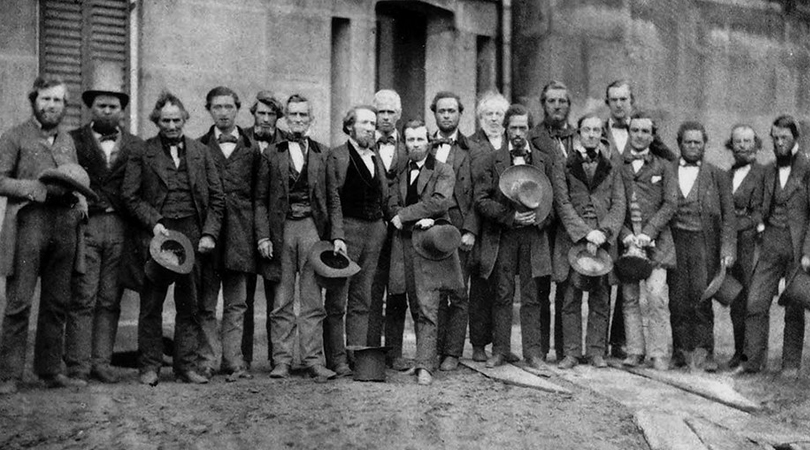

Cover image: Abolitionist men from Oberlin and Wellington, Ohio, who were charged with breaking the law after helping a freedom seeker in the fall of 1858. Courtesy: Oberlin College Archives.